- 15 NW Martin Luther King Jr. BLVD Evansville, IN 47708

- info@evansvillepolice.com

In 1812, Colonel Hugh McGary, Jr., purchased a 200 acre tract of land from the federal government and built a cabin on the end of what is present day Main Street. When Warrick County was established a few years later, McGary donated 100 acres to the county with the provision McGary’s land would be appointed as the county seat. But in 1814, the territorial legislature of Indiana divided Warrick County, creating Posey County on the west and Perry County on the east. Warrick County returned the donated land to McGary, relocating the seat of county government to Darlington—no longer in existence—which was more centrally located.

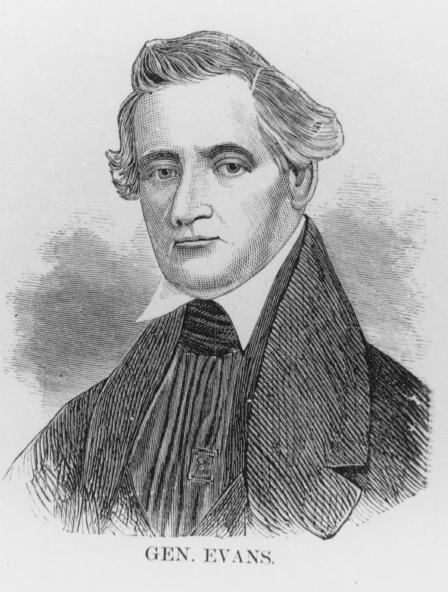

Until 1817, Evansville had progressed little beyond the status of village. Being “land poor”, McGary joined forces with General Robert M. Evans and Evans’ brother-in-law, James W. Jones, to expand growth of the city through the purchase of additional acreage. In its developmental stages, the town was called Evansville in honor of the general’s significant contributions. In 1818, Vanderburgh County was formed from the western portion of Warrick County and named for Judge Henry Vanderburgh, a Territorial Judge and early settler of Indiana. In that same year, commissioners were appointed to establish Evansville as the seat of justice for Vanderburgh County.

In 1847, Evansville was incorporated as a city and, in 1857, Evansville annexed the adjoining town of Lamasco. Lamasco had been developed by four investors—two with the surname Law, a Macoll, and one named Scott. It was at the end point of the Wabash and Erie Canal, bordered by the Ohio River, and what is now First Avenue to the east, Maryland Street to the north, and St. Joseph Avenue to the west. Lamasco had plotted its streets on cardinal points—true to north, south, east, and west. Conversely, Evansville had mapped its streets running parallel to the river. A legacy of the merger between Lamasco and Evansville may be what remains to be the confusion of Evansville’s centrally located streets. In addition, both towns had numbered streets and it was agreed that Lamasco would retain its numbered avenues—First, Second, etc.—but change the names of numbered streets to the names of states. Evansville kept its numbered streets, those that ran parallel to the river; i.e. SE First, NW Second, etc.

The history of the Evansville Police Department is linked, of course, to the development of the city. Law enforcement in Evansville began in 1818 and can be broken down into four phases.

The birth of the Evansville Police Department dates back to 1863 with the employment of two men assigned to the duty of checking downtown buildings at night. At the end of the Civil War in 1865, it became necessary for the community to enlarge its protective force and the department increased its number to sixteen and fell under the supervision of Evansville’s Mayor, William Baker. Because there were more officers to oversee, it became necessary to appoint a supervisor for the police department. As Phillip Klein had been “duly elected” the Wharfmaster, he was selected to be Captain of Police, receiving orders from the mayor who retained the position of Chief of Police.

Shortly after the appointment of Captain Klein, an emergency situation presented itself to the community. Prompted by civil unrest, the mayor and city council increased the ranks of the police department to number thirty-six men. After peace was restored, the force was again reduced to its original number of sixteen. Not only were these officers responsible for law enforcement, but served as the fire department as well.

In 1866, using their legislative powers, the City Council of Evansville began reorganization of the police department. It was put into law that the Wharfmaster and Deputy Marshals would control daytime policing while the Captain of Police and his officers had jurisdiction over nighttime enforcement. By 1869, the force had grown to twenty-three and was in need of a full time Chief of Police. Klein, who was then serving in the position of Marshal, resigned that position to accept an appointment as the first Chief of Police of the Evansville Police Department. Klein’s salary was set at $2.50 per day—a fifty-cent increase over the pay of his patrolmen. A police officer’s work day was twelve hours, seven days a week.

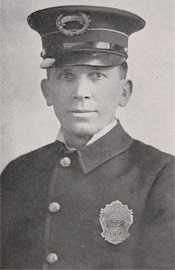

Frank Pritchett joined the Evansville Police Department in 1878. Shortly thereafter, he was appointed Deputy Chief Marshal and—in 1881—named Chief of Police, a position he held until 1886. It was during Pritchett’s tenure that the Indiana General Assembly passed the Metropolitan Police Act of 1883. This act provided for the Governor of Indiana to appoint three police commissioners for each city and charged them with the responsibility of running the force. The act also provided for the appointment of a Chief of Police, a captain, a sergeant, and one patrolman per one-thousand residents. The official census taken in Evansville in 1880 stood at 29,280 residents.

The Metropolitan Police Force would be in existence for only ten years and the police department occupied a small building near the entrance to City Hall. Under the Metropolitan Police Force and Chief Pritchett, many firsts were accomplished by the department. Requirements regarding physical attributes and general appearance were established and newspaper advertisements were used for the first time to recruit police personnel. A probation period was established for new officers and upon successful completion, a new policeman began his career at a starting salary of $14.00 per week.

In 1893 all city and town charters were revoked by the Indiana General Assembly and that body began its control of all corporations in the state. New acts of the State Legislature brought about new laws governing police departments, one of which established Boards of Public Safety comprised of three persons appointed by city government. Most police powers were given to that board. It also became law that the Chief of Police and Chief of the Fire Department had to be of opposite political parties. In conjunction with that edict, one half of the police department personnel had to be of one political party, half was to belong to the other.

By the turn of the century, the police department had established a Detective Bureau, and in 1900, began to mechanize some of its functions. Initially, two offers were assigned to ride bicycles and were called Emergency Officers. They were stationed at police headquarters and worked directly from there.

In 1905, the Indiana General Assembly again made changes to laws regarding Police and Fire Chiefs. These changes amended the law by stating it was no longer necessary for chiefs of these two entities to be of opposite political parties. In 1906, seventy-five Police Call Boxes were installed throughout the city. Each call box was connected to a switchboard at police headquarters and officers who walked beats were required to call in every hour to receive instruction. By 1908, the department had increased its bicycle force to six men and number of service horses to four. Police Matrons had also been added to the department at a salary of $520 per year. In addition to their assignment of taking care of female prisoners, they were also charged with the duty of food preparation for all prisoners.

Benjamin Bosse as Mayor of Evansville in 1914, the police department embarked on a mission to “…rejuvenate the department.” To achieve this ambition, Bosse named Edgar Schmitt to serve as Chief of Police. This was somewhat of an unorthodox appointment as Schmitt was selected from the rank and file, having served as a Patrolman, Bicycleman and Motorcycleman. Under Schmitt’s direction, there was a sense that the department had regained its dignity and professionalism. Schmitt also “rehabilitated” the Bertillion department and appointed John Heeger as Bertillion Officer. The Bertillion System was a criminal identification system known as anthropometry. In this system the person was identified by measurement of the head and body, individual markings—tattoos, scars—as well as personality characteristics. The measurements were made into a formula that would apply to only one person and would not change. Unlike contemporary forensic methods such as fingerprints identification, the Bertillion method did not always give an exact match. However, it did allow an investigator to narrow the pool of possible people to compare with the person in a photograph. The system was eventually found to be flawed and, ultimately, abandoned.

In 1915 construction began for the new police building at 200 SE Third Street and was completed and the structure dedicated in 1917. The police department was comprised of the Chief, a Chief of Detectives, two Captains, four Sergeants, seven Detectives, one Humane Officer, one Bertillon Officer, two Turnkeys, four Wagonmen, twelve Bicycle Officers, two Telephone Officers, and one Court Officer. In the early days of modernization, Bicycle Officers were stationed at certain hose houses and Beat Officers assigned to various districts. When needed, the beat officer was summoned to the Hose House by the tolling of a bell situated atop each fire house.

In 1926 the work day was shortened to eight hours though officers still worked a seven-day week. Radios were introduced in 1931, but were a far departure from the present system. Officers patrolled while listening to the local radio station and waited for the station announcer to interrupt the program and tell them where they were needed. Operators at police headquarters would receive a call by telephone, then relay information to the radio station. The radio broadcast would break off and the announcer call the car number and give specifics of the “run”. Then in 1935, the first Police Radio Communications was established. Police cars were equipped with two-way radios, but police motorcycles had only one-way communication. Officers riding motorcycles could hear only what the dispatcher at headquarters relayed, but could not hear transmission from other patrol cars.

In 1933, Mayor Frank Griese (1930-1935) devoted time and attention to the Boy’s Patrol movement which he—as mayor and member of the Automobile Club of Evansville—helped to sponsor. The program which is still in operation today under the supervision of the School Safety Unit, was originally part of the Traffic Division.

During the latter part of the first administration of Mayor William Dress, new systems of record keeping were introduced to expedite the handling and retaining of records in a number of city departments. Previously, police department records had been kept in books and handwritten by various clerks and police officers. Turnkeys also used the “slate” to keep track of prisoners in the city jail; the slate consisting of the top of a desk. All of the systems in place were insufficient and obsolete. The establishment of the Police Records Room started in 1938 through a Works Project Administration undertaking, the WPA being the largest of the New Deal agencies. With the aid of FBI officials, a number of forms were developed and fifty persons were assigned to the project which took nearly one year to complete.

In 1940, the Board of Public Safety exercised their authority over the police department with the development of a police training school. This was the first real step taken towards successful training of Evansville Police Officers. The school was conducted over a period of six months; the first two months took place in the classroom, the remaining four months were split between four hours in class and four hours performing actual police patrol. During this training period, officers earned approximately $20.00 per week.

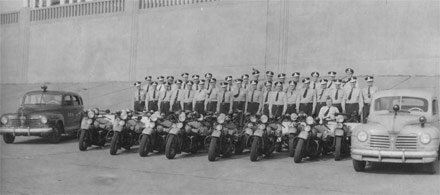

The beginning of World War II in 1941 created a new set of obstacles for the Evansville Police Department. Some officers enlisted or were drafted for military duty and replacements were difficult to find. Subsequently, the city hired a few men who worked “at the pleasure of the mayor” to help bridge the gap while officers were in the service. During the war, the police department took its responsibility as the first line of defense for the community very seriously. Officers were stationed at the main waterworks plant, electric plant, and other essential protected areas. While there was only one accident car to patrol the city, the Traffic Department had twenty-three motorcycles, each assigned to a specific officer.

During the years following the war, the department experienced few major alterations. Personnel levels expanded and the table of operations changed with each new administration.

In 1956, the department re-established its in-service training program. Since the police school program had ended just prior to the beginning of World War II, the department had been sending officers to outside training such as Purdue University. Lieutenant Alvah “Alvey” Simms was placed in charge of the new Training Unit.

However, the most significant change to the Evansville Police Department was yet to come with the end of the political patronage system of hiring. The merit statute had been enacted by the state legislature in 1957 and became law on January 1, 1958 and a three-member commission was established. Since that time officers have been hired and promoted on merit rather than on political patronage. But the merit system did not come into being quietly. There was a great deal of initial opposition to changing a system that had been around for 95 years. Mayor Vance Hartke, the chief of police and top commanders of the police department opposed it. Ronald Shively, a state representative from Evansville had pushed the bill through the legislature and the Fraternal Order of Police backed the legislation.

With the advent of the merit system, a unit was needed to act as liaison with the Merit Commission and conduct all the testing that would be required under such a system for both hiring and promoting. The personnel unit was established in 1958 with Lieutenant Alvah “Alvey” Simms becoming its first commander. The personnel function was merged with training and the unit was called the personnel and training unit. Later as the functions of the unit grew, the unit was divided into the personnel unit and the training unit.

The merit system established maximum and minimum age requirements. The maximum age was set at 65. Officers over 65 were allowed to remain on the department until the end of 1958. The system also established a 40-hour workweek for officers. Some of the ranks within the department were reorganized and the position of assistant chief was reestablished after an absence of five years. Everett McIntire was appointed to the position of Assistant Chief.

The first applicant school, conducted by the Merit Commission, occurred from December 1 to 8, 1958. The school consisted of ten hours of training with a written test based on subjects taught in the school. The Merit Commission also conducted interviews. The Personnel and Training Unit, in conjunction with the Merit Commission administered the school and tests. Height requirements fell between 5’9” and 6’5” inches and the weight requirements between 150 and 230 pounds. Age limits were 23 to 33 years-of-age.

Just prior to the implementation of the merit system, the Safety Board ordered a complete reorganization of the police department. The rank of Chief of Detectives was eliminated and the Detective Bureau became the Criminal Investigations Division with an Inspector in charge.